Alsace-Lorraine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

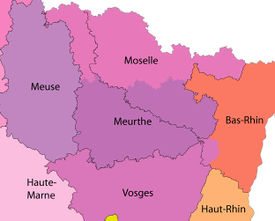

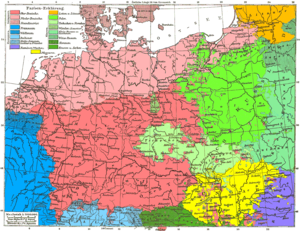

Alsace-Lorraine (German: Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen, generally Elsass-Lothringen) was a territory created by the German Empire in 1871 after the annexation of most of Alsace and the Moselle region of Lorraine in the Franco-Prussian War. The Alsatian part lay in the Rhine Valley on the west bank of the Rhine River and east of the Vosges Mountains. The Lorraine section was in the upper Moselle valley to the north of the Vosges Mountains.

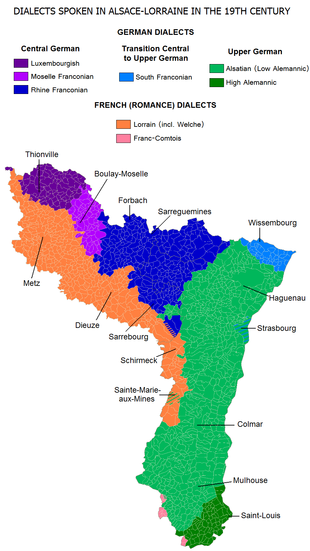

These territories had become part of Eastern Francia in 921 during the reign of King Louis the German, and later became part of the Holy Roman Empire. Their population spoke Germanic and Romance dialects. Those in Alsace spoke in their vast majority Germanic dialects, in particular Alsatian, an Alemannic German dialect similar to that spoken on the opposite bank of the Rhine, while those in Lorraine were divided roughly equally between those who spoke the Romance Lorrain dialect and those who spoke Franconian German dialects. The area had gradually become part of France between 1552, when Metz was ceded to the Kingdom of France, and 1798, when the Republic of Mulhouse joined the French Republic. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the area was annexed by the newly-created German Empire in 1871 by the Treaty of Frankfurt and became a Reichsland.

French troops entered Alsace-Lorraine in November 1918 at the end of the World War I and the territory reverted to France at the Treaty of Versailles of 1919.

The area was de facto annexed by Nazi Germany in 1940 (although no official de jure annexation took place), but reverted to France in 1944-1945 at the end of World War II and has remained a part of France since.

In 1871, the Reichsland of Elsaß-Lothringen was made up of 93% of Alsace (7% remained French) and 26% of Lorraine (74% remained French). For historical reasons, specific legal dispositions are still applied in the territory in form of a local law. In relation to its special legal status, the territory has since its reversion to France been referred to as Alsace-Moselle.[1]

Geography

The Imperial Province of Alsace-Lorraine had a land area of 14,496 km² (5,597 square miles). Its capital was Strasbourg. It was divided in three districts (Bezirke in German):

- Upper Alsace (Oberelsaß), whose capital was Colmar, had a land area of 3,525 km² and corresponds exactly to the current department of Haut-Rhin.

- Lower Alsace (Unterelsaß), whose capital was Strasbourg, had a land area of 4,755 km² and corresponds exactly to the current department of Bas-Rhin.

- Lorraine (Lothringen), whose capital was Metz, had a land area of 6,216 km² and corresponds exactly to the current department of Moselle.

Towns and cities

The largest urban areas in Alsace-Lorraine at the 1910 census were:

- Straßburg: 220,883 inhabitants

- Mülhausen: 128,190 inhabitants

- Metz: 102,787 inhabitants

- Diedenhofen: 69,693 inhabitants

- Kolmar: 44,942 inhabitants

History

Ancient and medieval history

Always closely tied to the Rhine River, which forms its eastern boundary, Alsace has been a border region for most of its history. It was first conquered by Julius Caesar in the first century B.C. and remained a part of the Roman province of Prima Germania for the following six centuries. The region was conquered by the Alemanni, a Germanic tribe, in the fifth century A.D. and then by Clovis and the Franks in 496. Under his Merovingian successors, the inhabitants were Christianized.

In the ninth century, this region became part of the heartland of the Carolingian Empire of Charlemagne (Charles the Great). When Charlemagne's grandsons divided his empire at the Treaty of Verdun of 843, the region was in the middle of Lorraine (Lotharingia), part of a narrow middle strip granted to Lothar with German- and French-speaking kingdoms to either side. Buffeted on both sides, the new kingdom did not last long and the region that was to become Alsace fell to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation as part of the duchy of Swabia in the Treaty of Meersen in 870. At about this time the entire region began to fragment into secular and ecclesiastical lordships, a situation that lasted into the 17th century and was a common process in Europe.

One of the most powerful secular families of Swabia was that of the Staufen or Hohenstaufen. In 1152, this family placed its leading member on the German throne as Friedrich I Barbarossa. Frederick was instrumental in the recovery of the monarchy from its dissipation following the Investiture Contest. Part of the reason was his policy of building up imperial lands in support of the monarchy and in 1212, Alsace was organized for the first time as we know it today as one of those lands. Frederick set up Alsace as a province (though not provincia but procuratio was used) to be ruled by ministeriales, a non-noble class of civil servants. The idea was that such men would be more tractable and less likely to alienate the fief from the crown out of their own greed. The province had a single provincial court (Landgericht) and a central administration, with its seat at Haguenau.

During his reign, Emperor Friedrich II designated the bishop of Strasbourg to administer Alsace, but the authority of the bishop was challenged by Count Rudolf of Habsburg, who received his rights from Friedrich's son Conrad IV. Strasbourg, which had been an episcopal see since the fourth century, began to grow, becoming the most populous and commercially important town in the region. In 1262, after a long struggle with the ruling bishops, its citizens gained for it the status of free imperial city. A stop on the Paris-Vienna-Orient trade route, as well as a port on the Rhine route linking southern Germany and Switzerland to the Netherlands, England and Scandinavia, it became the political and economic center of the region. Cities such as Colmar and Haguenau also began to grow in economic importance and gained a kind of autonomy within the "Decapole" or "Dekapolis", a federation of ten free towns.

Around this time, German central power declined following years of imperial adventures in Italian lands, which ceded hegemony in Europe to France, long a centralized power. Now France began an aggressive policy of expanding eastward, first to the Rhône and Meuse Rivers, and when those borders were reached, to the Rhine. In 1299, France even proposed a marriage alliance between Philip IV of France's sister and Albrecht of Austria's son, with Alsace to be the dowry; however, the deal never materialized. In 1307, the town of Belfort was first chartered by the counts of Montbéliard.

During the next century, France was militarily shattered by the Hundred Years War with England, which prevented for a time any further tendencies in this direction. After the conclusion of the war, France was again free to pursue its desire to reach the Rhine, and in 1444 a French army appeared in Lorraine and Alsace, where it took up winter quarters, demanded the submission of Metz and Strasbourg, and launched an attack on Basel.

Modern history

In 1469, following the Treaty of St. Omer, Upper Alsace was sold by Duke Sigismund of Habsburg to Charles of Burgundy who also ruled over the Netherlands and Burgundy. Although Charles was the nominal landlord, taxes were paid to the German Emperor. The Emperor was able to use this tax and a dynastic marriage to regain full control of Upper Alsace (apart from the free towns, but including Belfort) in 1477 when it became part of the particular demesne of the Habsburg family, who were the hereditary rulers of the Empire. Later, in 1515, the town of Mulhouse joined the Swiss Confederation, where it remained until 1798.

By the time of the Reformation in the 16th century, Strasbourg was a prosperous community, and its inhabitants accepted Protestantism at an early date (1523). The reformer Martin Bucer was a prominent Protestant reformer in the region. His efforts were countered by the Roman Catholic Habsburgs who tried to eradicate Protestant heresy in Upper Alsace. As a result, Alsace was transformed into a mosaic of Catholic and Protestant territories.

This situation prevailed until 1639, when most of Alsace was conquered by France to prevent it from falling into the hands of the Spanish Habsburgs who wanted a clear road to their valuable and rebellious possessions in the Netherlands. This occurred in the context of the Thirty Years War. So, in 1646, beset by enemies and to gain a free hand in Hungary, the Habsburgs sold their Sundgau territory (mostly in Upper Alsace) to France, for the sum of 1.2 million thalers. Thus, when the hostilities ceased in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia, most of Alsace went to France with some towns remaining independent. The treaty stipulations regarding Alsace were extremely confusing; it is thought that this was done purposely so that neither the French king nor the German Emperor could gain tight control, but that one would play off the other, thereby assuring Alsace some measure of autonomy. Supporters of this theory point out that the treaty stipulations were authored by Imperial plenipotentiary Isaac Volmar, the former chancellor of Alsace.

The Thirty Years War (1618–1648) had been one of the worst periods in the history of Alsace and other parts of Southern Germany. It caused large numbers of the population (mainly in the countryside) to die or to flee when the land was successively invaded and devastated by many armies (Imperials, Swedes, French, etc.). After 1648 and until the mid-18th century, numerous immigrants arrived from Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Lorraine, Savoy and other areas. Between 1671 and 1711, Anabaptist refugees came from Switzerland, especially from Bern. Strasbourg became a center of the early Anabaptist movement.

France consolidated its hold on Alsace with the 1679 Treaties of Nijmegen, which brought the towns under its control. In 1681, France occupied Strasbourg in an unprovoked action. These territorial changes were reinforced at the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick which ended the War of the Palatinate (also known as the War of the Grand Alliance or War of the League of Augsburg), although the Holy Roman Empire did not accept and sign the document until 1697. Thus was Alsace drawn into the orbit of France. However, Alsace had a somewhat exceptional position in the kingdom. The German language was still used in local government, school and education and the German (Lutheran) university of Strasbourg was attended by students from Germany. The Edict of Fontainebleau, which legalized the brutal suppression of French Protestantism, was not applied in Alsace, and in contrast to the rest of France there was a relative religious tolerance (although the French authorities tried to promote Catholicism and the Lutheran Strasbourg Cathedral had to be handed over to the Catholics in 1681). There was a customs boundary along the Vosges mountains against the rest of France, while there was no such boundary against Germany. For these reasons Alsace remained culturally and economically oriented towards Germany until the French Revolution.

The year 1789 brought the French Revolution and with it the first division of Alsace into the départements of Haut- and Bas-Rhin. Alsatians played an active role in the French Revolution. On July 21, 1789, after receiving news of the Storming of the Bastille in Paris, a crowd stormed the Strasbourg city hall, forcing the city administrators to flee and putting a symbolic end to the feudal system in Alsace. In 1792, Rouget de Lisle composed in Strasbourg the Revolutionary marching song La Marseillaise, which later became the anthem of France. La Marseillaise was played for the first time in April of that year in front of the mayor of Strasbourg Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich. Some of the most famous generals of the French Revolution also came from Alsace, notably Kellermann, the victor of Valmy, and Kléber, who led the armies of the French Republic in Vendée.

At the same time, some Alsatians were in opposition to the Jacobins and sympathetic to the invading forces of Austria and Prussia who sought to crush the nascent revolutionary republic. Many of the residents of the Sundgau made "pilgrimages" to places like Mariastein Abbey, near Basel, in Switzerland, for baptisms and weddings. When the French Revolutionary Army of the Rhine was victorious, tens of thousands fled east before it. When they were later permitted to return (in some cases not until 1799), it was often to find that their lands and homes had been confiscated. These conditions led to emigration by hundreds of families to newly-vacant lands in the Russian Empire in 1803-4 and again in 1808. A poignant retelling of this tale based on what he had himself witnessed can be found in Goethe's Hermann und Dorothea.

In response to the restoration of Napoleon I of France, in 1814 and 1815, Alsace was occupied by foreign forces, including over 280,000 soldiers and 90,000 horses in Bas-Rhin alone. This had grave effects on trade and the economy of the region, since former overland trade routes were switched to newly-opened Mediterranean and Atlantic seaports.

The population grew rapidly, from 800,000 in 1814 to 914,000 in 1830 and 1,067,000 in 1846. The combination of factors meant hunger, housing shortages and a lack of work for young people. Thus, it is not surprising that people left Alsace, not only to Paris, where the Alsatian community grew in numbers, with famous members such as Baron Haussmann, but also to far away places like Russia and the Austrian Empire to take advantage of new opportunities offered there. Austria had conquered lands in Eastern Europe from the Ottoman Empire and offered generous terms for colonists in order to consolidate their hold on the lands. Many Alsatians also began to sail for the United States.

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871

_Elsaß-Lothringen.svg.png)

The newly-created German Empire's demand of territory from France in the aftermath of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War was not simply a punitive measure. The transfer was controversial even amongst the Germans themselves - German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck was strongly opposed to a transfer of territory that he knew would provoke permanent French enmity towards the new state. However, German Emperor Wilhelm I eventually sided with Helmuth von Moltke the Elder and other Prussian generals and others who argued that a westward shift in the new Franco-German border was necessary and desirable for a number of reasons. From a nationalistic perspective, the transfer seemed justified, since most of the lands that were annexed were populated by people who spoke Alemannic German dialects. From a military perspective, shifting the Franco-German frontier away from the Rhine would give the Germans a strategic advantage over the French, especially by early 1870s military standards and thinking. Indeed, thanks to this annexation, the Germans took control of the fortifications of Metz, which was at the time a French-speaking town, and also of most of the iron resources available in the region.

However, domestic politics of the new Empire might have been the decisive factor. Although it was effectively led by Prussia, the German Empire was a new and highly decentralized creation. The new arrangement left many senior Prussian generals with serious misgivings about leading diverse military forces to guard a pre-war frontier that, except for the northernmost section was part of two other states of the new Empire - Baden and Bavaria. As recently as the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, these states had been Prussia's enemies. Both states, but especially Bavaria had been given substantial concessions with regards to local autonomy in the new Empire's constitution, including a great deal of autonomy over military matters. For this reason, the Prussian General Staff argued that it was prudent and necessary that the new Empire's frontier with France be under their direct control. Creating a new Imperial Territory (Reichsland) out of formerly French territory would achieve this goal: although a Reichsland would not be part of the Kingdom of Prussia, being governed directly from Berlin it would be under Prussian control. Thus, by annexing territory Berlin was able to avoid delicate negotiations with Baden and Bavaria on such matters as construction and control of new fortifications, etc. The governments of Baden and Bavaria, naturally, were in favour of moving the French border away from their territories.

It is important to note that memories of the Napoleonic Wars were still quite fresh in the 1870s. Right up until the Franco-Prussian War, the French had maintained a long-standing desire to establish their entire eastern frontier on the Rhine, and thus they were viewed by most 19th century Germans as an aggressive, war-mongering people. In the years prior to 1870, it is arguable that the Germans feared the French more than the French feared the Germans. Many Germans at the time thought creation of the new Empire in itself would be enough to earn permanent French enmity, and thus desired a defensible border with their old enemy. Any additional enmity that would be earned from territorial concessions was downplayed as marginal and insignificant in the overall scheme of things.

The annexed area consisted of the northern part of Lorraine, along with Alsace. Not affected by this was the town of Belfort and the area around it (now the French département of Territoire de Belfort), because their inhabitants were predominantly native French speakers and because Belfort has been heroically defended by Colonel Denfert-Rochereau, who surrendered only after receiving orders from Paris. The town of Montbéliard and its surrounding area to the south of Belfort, which have been part of the Doubs department since 1816, and therefore were not considered part of Alsace, were not included, despite the fact that they were a Protestant enclave, as it belonged to Württemberg from 1397 to 1806. This area corresponded to the French départements of Bas-Rhin (in its entirety), Haut-Rhin (except the area of Belfort and Montbéliard), and a small area in the northeast of the Vosges département, all of which made up Alsace, and the départements of Moselle (four-fifths of it) and the northwest of Meurthe (one-third of Meurthe), which were the eastern part of Lorraine.

The remaining département of Meurthe was joined with the westernmost part of Moselle which had escaped German annexation to form the new département of Meurthe-et-Moselle.

The new border between France and Germany mainly followed the geolinguistic divide between Romance and Germanic dialects, except in a few valleys of the Alsatian side of the Vosges mountains, the city of Metz and in the area of Château-Salins (formerly in the Meurthe département), which were annexed by Germany despite the fact that people there spoke French[2]. In 1900, 11.6% of the population of Alsace-Lorraine spoke French as mother language (11.0% in 1905, 10.9% in 1910).

The fact that small francophone areas were affected was used in France to denounce the new border as hypocrisy, since Germany had justified them by the native Germanic dialects and culture of the inhabitants, which was true for the majority of Alsace-Lorraine. However, the German administration was tolerant of the use of the French language, and French was permitted as an official language and school language in those areas where it was spoken by a majority (this relatively tolerant policy contrasted with the policy of French authorities against the use of German after World War I).

The Treaty of Frankfurt gave the residents of the region until October 1, 1872 to choose between emigrating to France or remaining in the region and having their nationality legally changed to German. By 1876, about 100,000 or 5% of the residents of Alsace-Lorraine had emigrated to France.[3]

The "being French" feeling stayed strong at least during the first sixteen years of the annexation. During the Reichstag elections, the fifteen deputies of 1874, 1881, 1884 (but one) and 1887 were called protester deputies (fr: députés protestataires) because they expressed to the Parliament their opposition to the annexation by means of the 1874 motion in French language: « May it please the Reichstag to decide that the populations of Alsace-Lorraine that were annexed, without having been consulted, to the Germanic Empire by the treaty of Frankfurt have to come out particularly about this annexation[4]. »

Under the German Empire of 1871-1918, the territory constituted the Reichsland or Imperial Province of Elsass-Lothringen. The area was administered directly by the imperial government in Berlin and was granted some measure of autonomy in 1911. This included its own flag, and the Elsässisches Fahnenlied as anthem. The infamous Saverne Affair (1913), however, showed that this status was of no high value in the eyes of the Berlin government.

Reichstag election results 1874-1912

| 1874 | 1877 | 1878 | 1881 | 1884 | 1887 | 1890 | 1893 | 1898 | 1903 | 1907 | 1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhabitants (in 1,000) | 1550 | 1532 | 1567 | 1564 | 1604 | 1641 | 1719 | 1815 | 1874 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eligible voters (in %) | 20.6 | 21.6 | 21.0 | 19.9 | 19.5 | 20.1 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 21.9 | 22.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout (in %) | 76.5 | 64.2 | 64.1 | 54.2 | 54.7 | 83.3 | 60.4 | 76.4 | 67.8 | 77.3 | 87.3 | 84.9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conservatives (K) | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 4.8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deutsche Reichspartei (R) | 0.2 | 12.0 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 6.1 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National Liberal Party (N) | 2.1 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 11.5 | 8.5 | 3.6 | 10.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Liberals | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Freeminded Union (FVg) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 6.2 | 6.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Progressive People's Party | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 14.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Centre Party (Zentrum) (Z) | 0.0 | 0.6 | 7.1 | 31.1 | 5.4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Social Democratic Party of Germany (S) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 10.7 | 19.3 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 23.7 | 31.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regional Parties (Autonomists) (Aut) | 96.9 | 97.8 | 87.5 | 93.3 | 95.9 | 92.2 | 56.6 | 47.7 | 46.9 | 36.1 | 30.2 | 46.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1874 | 1877 | 1878 | 1881 | 1884 | 1887 | 1890 | 1893 | 1898 | 1903 | 1907 | 1912 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mandates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FVp: Progressive People's Party. formed in 1910 as a merger of all leftist liberal parties.

During World War I

[Translation of Pendant la Grande Guerre]

Alsace-Lorraine, during this time, was a geo-political prize contested between the French and German powers. With the increased militarization of Europe, coupled with the lack of negotiation between major powers, led to harsh and rash actions taken by both parties in respect to Alsace-Lorraine.

As soon as war was declared, both French and German sides made mistakes and insults towards Alsace-Lorraine people, who were used as pawns in the growing conflict between France and Germany.

Alsatians living in France were arrested and dragged into camps with popular French support; besides, when Frenchmen got into a village, they wildly arrested people, taking sometimes old medallist veterans of 1870[5]. The Germans responded with worse atrocities : the Saverne Affair had convinced the high command that the whole population was intensely hostile to the German Reich and that it should be terrorized into submission.

Due to the proximity of the front, German troops confiscated homes. The German military were highly suspicious of French patriots.

Whereas German authorities usually had been relatively tolerant with the use of French, they started to develop policies aimed at reducing the influence of French. French street names in Metz, which were displayed before in both languages, were suppressed on January 14, 1915. Six months later, on July 15, 1915, German became the only official language in the region[6], leading to the Germanification of the towns’ names by an order of September 2, 1915.

Prohibiting the speaking of French in public further increased the exasperation of the natives, who were long accustomed to mix up their conversation with French language (see code-switching); however, the use even one word, as innocent as "bonjour", could incur a fine[7].

The non-native Germans believed to show patriotism while taking part in the hunting: they had fine hearing to denounce to the police all that they heard in the cursed language. Thus, the population was divided between an all-powerful minority and a majority which could only keep its fist in its pocket and wait for the hour of revenge[8].

German authorities became increasingly worried about this renewed French patriotism, as Reichslands governor stated it in February 1918: "Sympathies towards France and repulsion for Germans have penetrated to a scary depth the petty bourgeoisie and the peasantry".[9]

Regarded as suspect, the Alsatian or Lorraine soldier was obviously sent on the Russian front where the most dangerous missions were assigned to him. The permissions were granted to him less easily than to other German soldiers[10]. Anyway, even if he obtained his permission, the Alsatian-Lorraine soldier had to wait three weeks to let the local police investigate his family[11].

If he lived too close to the Swiss border, it was feared too much that he would try to desert and he had to remain in Baden, where his family was liberally given the right to come and see him[12].

After World War I

- See also Alsace Soviet Republic

In order to spare them possible confrontations with relatives in France, the soldiers from Alsace-Lorraine were mainly sent to the Eastern front, or the Kaiserliche Marine.

In October 1918, the German Imperial Navy, which had spent most of the war since the Battle of Jutland in ports, was ordered to fight, in order to weaken the British Royal Navy for the time after the war. However, the sailors refused to obey. At that time, about 15,000 Alsatians and Lorrainers had been incorporated into the Kaiserliche Marine. Some of them joined the insurrection and the German Revolution, and decided to rouse their homeland to revolt against the monarchy of the Emperor.

Independent Republic of Alsace-Lorraine

On 8 November 1918, the proclamation of a Soviet Republic in Bavaria was aired in Strasbourg, the capital city of Alsace. The next day, on November 9, thousands of demonstrators rallied at the local bakers square in Strasbourg, to acclaim the first soldiers returning home from northern Germany. A train controlled by insurgents was blocked on the Kehl bridge, and a loyal commander ordered to fire on the train. One insurgent was killed, but his fellows took control of the city of Kehl.

The same day, Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated and Philipp Scheidemann declared Germany a republic in a speech from the Reichstag. As Alsace-Lorraine had been administered by Berlin and the Emperor, and had no state government and monarch like other German states, the departure of the Emperor left an even larger vacuum of power.

Similar to other areas of Germany, the former seamen established a Soldiers' Council of Strasbourg, and took the control of the city. A council of workers and soldiers was then established and presided by the leader of the brewery workers' union. Their motto was: 'Neither German nor French nor neutral.'

On 11 November, the Armistice with Germany (Compiègne) was signed, ending the war. The same day, the Diet of Strasbourg proclaimed an Independent Republic of Alsace-Lorraine. The Landtag (parliament) proclaimed itself the "National Council of Alsace-Lorraine" and the sole legal authority there. The next day, the National Council took over all functions of the Statthalter and of the Secretary of state, and proclaimed the sovereignty of Alsace-Lorraine. Eugène Ricklin and Jacques Peirotes were in charge.

Independence was short-lived as the French occupied Mülhausen on 17 November. They took Colmar and Metz on the next days, and, on 21 November 1918, French troops arrived in Strasbourg.

After the Republic of Alsace-Lorraine

After eleven days of independence, Alsace-Lorraine was occupied by and incorporated into France. The region lost its recently acquired autonomy, was returned to the centralised French system and divided into the départements of Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin and Moselle (the same political structure as before the annexation and as created by the French Revolution, with slightly different limits).

Today the territory enjoys laws in certain areas that are significantly different from the rest of France - these specific provisions are known as the local law.

The département Meurthe-et-Moselle was maintained even after France recovered Alsace-Lorraine in 1919. The area of Belfort became a special status area and was not reintegrated into Haut-Rhin in 1919 but instead was made a full-status département in 1922 under the name Territoire-de-Belfort[13].

Expulsion of Germans

The French Government immediately started a Francization campaign that included the forced deportation of all Germans who had settled in the area after 1870. For that purpose, the population was divided in four categories, A to D[14]. German-language Alsatian newspapers were also suppressed.

World War II

After France was defeated in the spring of 1940, the area was administered from Berlin by the Germans until they were defeated in 1945. During the occupation, all inhabitants of military age were subject to conscription into the German army, and in some cases engaged in repression against French citizens during the Second World War (see for instance the massacre of Oradour-sur-Glane).

About 130,000 young men from Alsace-Lorraine were also drafted or volunteered to serve in the German Wehrmacht or the Waffen-SS during the Second World War, mostly on the eastern front (40,000 of them were killed or missing in action). This led to numerous problems and recriminations after the war.

Contemporary history

When Alsace-Lorraine was returned to France after the war, the fact that many young men from the area had served (mostly by force) in the German Army, and even the Waffen SS, resulted in tensions between Alsace-Lorraine and other parts of France.

The French government pursued, in line with its traditional language policy, a campaign to suppress the use of German. Both the German language as well as the local dialects Alsatian, Moselle Franconian, Lorraine Franconian and Luxembourgish Franconian were for a time banned from public life (street and city names, official administration, the educational system, etc.). Largely due to this policy, Alsace-Lorraine is today very French in language and culture. Few young people speak one of the Franconian dialects today or Alsatian, though the closely-related Alemannisch survives on the opposite bank of the Rhine, in Baden, and especially in Switzerland. However, while French is the major language of the region, the Alsatian dialect of French is heavily influenced by German in phonology and vocabulary.

In recent times, official and private initiatives have been trying to reverse this process to preserve the area's unique Franco-German cultural heritage. For instance, French high schools students can apply to attend a specific class entitled "Langue régionale d'alsace et des pays mosellans" (Regional language of Alsace and Moselle countries)[15]. However, French officials chose in 2008 to suppress fundings for bilingual electoral propaganda, which had been existing since 1919[16]. France is one of four nations (together with Andorra, Monaco, and Turkey) that has never signed the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities[17].

Demographics

| Year | Population | Cause of change |

|---|---|---|

| 1866 | 1,596,198 | - |

| 1875 | 1,531,804 | After incorporation into the German Empire, 100,000 to 130,000 people left for France and French Algeria |

| 1910 | 1,874,014 | 0.58% population growth per year during 1875-1910 |

| 1921 | 1,709,749 | Death of young men in the German army, Deportation of German newcomers to Germany by the French authorities |

| 1936 | 1,915,627 | 0.76% population growth per year during 1921-1936 |

| 1946 | 1,767,131 | Death of young men in the French army in 1939-40, Death of young men in the German army in 1942-45, Death of civilians and many people still refugees in the rest of France |

| 1999 | 2,756,931 | 0.84% population growth per year during 1946-1999 |

| 2008 | 2,877,000 | 0.48% population growth per year during 1999-2008 |

Languages

Both Germanic and Romance dialects were traditionally spoken in Alsace-Lorraine before the 20th century.

Germanic dialects:

- Central German dialects:

- Luxembourgish Franconian in the north-west of Moselle (Lothringen) around Thionville (Diddenuewen in the local Luxembourgish dialect) and Sierck-les-Bains (Siirk in the local Luxembourgish dialect)

- Moselle Franconian in the central northern part of Moselle around Boulay-Moselle (Bolchin in the local Moselle Franconian dialect) and Bouzonville (Busendroff in the local Moselle Franconian dialect)

- Rhine Franconian in the north-east of Moselle around Forbach (Fuerboch in the local Rhine Franconian dialect), Bitche (Bitsch in the local Rhine Franconian dialect), and Sarrebourg (Saarbuerj in the local Rhine Franconian dialect), as well as in the north-west of Alsace around Sarre-Union

- Transitional between Central German and Upper German:

- South Franconian in the northernmost part of Alsace around Wissembourg (Waisseburch in the local South Franconian dialect)

- Upper German dialects:

- Alsatian in the largest part of Alsace and in a few villages in the extreme east of Moselle. Alsatian was the most spoken dialect in Alsace-Lorraine.

- High Alemannic in the southernmost part of Alsace, around Saint-Louis and Ferrette (Pfirt in the local High Alemannic dialect)

Romance dialects (belonging to the langues d'oïl like French):

- Lorrain in roughly the southern half of Moselle, including its capital Metz, as well as in some valleys of the Vosges Mountains in the west of Alsace around Schirmeck and Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines

- Franc-Comtois in 12 villages in the extreme south-west of Alsace

See also

- Alsace

- Censorship

- Cultural Assimilation

- Duchy of Alsace

- Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

- Irredentism

- Language policy in France

- Lorraine (province)

- Lorraine (region)

Further reading

- Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (2008). Boches ou tricolores. Strasbourg, France.

- Putnam, Ruth. Alsace and Lorraine from Cæsar to Kaiser, 58 B.C.-1871 A.D. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1915.

Notes

- ↑ An instruction dated 8.14.1920 from the assistant Secretary of State of the Presidency of the Council to the General Commissioner of the Republic in Strasbourg reminds that the term Alsace-Lorraine is prohibited and must be replaced by the sentence "the département of Haut-Rhin, the département of Bas-Rhin and the département of Moselle". While this sentence was considered as too long, some used the term Alsace-Moselle to point to the three concerned départements. However, it has no legal status because it can't point to any territorial authority.

- ↑ In fact, the linguistic border ran on the north of the new one, including in the "Alemannic" territories Thionville (also named Diedenhofen under the German Reich), Metz, Château-Salins, Vic-sur-Seille and Dieuze, which were fully French-speaking. The valleys of Orbey and Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines were in the same case. Similarly, the town of Dannemarie (and adjoining areas) were also left in Alsace when language alone could have made them part of Territoire de Belfort.

- ↑ http://www.mtholyoke.edu/~jihazel/pol116/annexation.html

- ↑ Les députés "protestataires" d'Alsace-Lorraine (French)

- ↑ In 1914, Albert Schweitzer was put under supervision in Lambaréné (then in French Equatorial Africa); in 1917, he was taken to France and incarcerated until July 1918.

- ↑ Grandhomme, Jean-Noël (2008) Boches ou tricolores. Strasbourg: La nuée bleue.

- ↑ As of on October 26, 1914, we can read in Spindler's journal: "Then he recommends to me not to speak French. The streets are infested with informers, men and women, who touch rewards and make arrest the passers by for a simple « merci » said in French. It goes without saying that these measures excite the joker spirit of the people. A woman at the market, who probably was unaware that "bonchour" and "merci" was French, is taken with part by a German woman because she answered her "Guten Tag" by a "bonchour ". Then, the good woman, the fists on the hips, challenges her client : "Now I'm fed up with your silly stories! Do you know what? [here somesthing like "kiss my ..."]! Is that endly also French? » (als: Jetz grad genua mit dene dauwe Plän! Wisse Sie was? Leeke Sie mich ...! Esch des am End au franzêsch?)"

- ↑ We can read in L'Alsace pendant la guerre how the exasperation of the population gradually increased but Spindler hears, as of on September 29, 1914, a characteristic sentence: « ... the interior decorator H., who repairs the mattresses of the Ott house, said to me this morning: “If only it was the will of God that we became again French and that these damned "Schwowebittel" were thrown out of the country! And then, you know, there are chances that it happens.” It is the first time since the war I hear a simple man expressing frankly this wish. »

- ↑ Grandhomme, Jean-Noël. op.cit.

- ↑ In May 1918, the deputies Jacques Peirotes, Boehle and Fuchs asked this question to the chancellor: « In spite of the orders emanating of the Ministry for the War, lifting the general suspension of the permissions for the soldiers of the German army, the Alsatian-Lorraine soldiers obtain only very rarely the permissions to which they have right. Is Mr Chancellor informed of this situation and is he ready to do what is necessary for the soldiers of Alsatian-Lorraine origin to be treated in the same way that are the soldiers of the other provinces of the Empire? »

- ↑ In June 1918, the deputy Boehle protested against the way this was treated: « In Strasbourg, for a long time it was an average policeman which was designated to make this investigation. This man took account of all the contentions that the concerned could have had in the past with the police and all was interpreted in a political way. »

- ↑ Mülhäuser Volkszeitung of June 8, 1918

- ↑ However on the Colmar prefecture building, the name of Belfort can be seen as a sous-prefecture.

- ↑ "Tabellarische Geschichte Elsaß-Lothringens / Französische Besatzung (1918-1940)". Archived from the original on 2009-10-25. http://www.webcitation.org/5kmXUnBss.

- ↑ http://www.education.gouv.fr/bo/2008/3/MENE0773513A.htm

- ↑ http://www.senat.fr/questions/base/2008/qSEQ080203265.html

- ↑ http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/ChercheSig.asp?NT=157&CM=&DF=&CL=ENG

External links

- http://www.geocities.com/bfel/geschichte5b.html (Archived 2009-10-25) (German)

- http://www.elsass-lothringen.de/ (German)

- http://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Rotunda/2209/Alsace_Lorraine.html

- France, Germany and the Struggle for the War-making Natural Resources of the Rhineland

- Elsass-Lothringen video

- AlsaceLorraine.info

|

||||||||||||||||||||||